Flavor is one of the most fascinating yet mysterious aspects of human experience. A single bite can evoke childhood memories, cultural identity, or sheer delight—or repulsion. But have you ever wondered why some flavors are immediately loved by nearly everyone, while others demand time, exposure, and patience to truly enjoy? These challenging flavors are often labeled as “acquired tastes.” From pungent cheeses to bitter brews, the journey to appreciation reveals a blend of biology, psychology, and culture.

In this article, we will explore why certain flavors are considered acquired tastes, diving into the interplay of our evolutionary biology, sensory perception, societal conditioning, and personal experience.

1. The Biology of Taste: A Survival Mechanism

The foundation of acquired taste begins with human biology. Taste is not just about pleasure; it is a survival mechanism shaped over millions of years. Humans have five primary taste sensations: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. Each serves a distinct evolutionary purpose:

- Sweet signals energy-rich foods, such as fruits and honey. It is universally appealing because calories were historically scarce.

- Salty indicates essential minerals. Sodium is vital for bodily function, so salt triggers natural cravings.

- Sour often warns of unripe or spoiled foods. Moderate sourness can be pleasant, but extreme acidity can trigger avoidance.

- Bitter frequently signals toxins. Many poisonous plants taste bitter, which explains why humans instinctively recoil from bitterness.

- Umami (savory) highlights protein-rich foods, guiding humans toward nutrient-dense options.

Because bitterness often indicates potential danger, it is naturally one of the hardest flavors to enjoy initially. Foods like black coffee, kale, dark chocolate, or certain herbal liqueurs often trigger a “yuck” reflex at first. Over time, however, repeated exposure and cultural reinforcement can transform this aversion into preference.

2. The Role of Genetics in Taste Perception

Not everyone experiences flavors in the same way. Genetics play a substantial role in shaping taste perception, particularly with bitterness. Research has identified a genetic marker, PROP taster status, which determines how intensely someone perceives bitter compounds. People fall into three categories:

- Non-tasters: Weak sensitivity to bitterness; often more willing to enjoy bitter vegetables.

- Medium tasters: Moderate sensitivity; may acquire tastes more slowly.

- Supertasters: Extremely sensitive to bitterness; may struggle with bitter foods for life.

This genetic variation explains why some individuals love the sharp tang of grapefruit, the earthy bite of arugula, or the deep complexity of a strong IPA, while others cannot tolerate them. An acquired taste, therefore, is partially a negotiation between genetics and exposure.

3. Cultural Conditioning: Flavor as Social Identity

Taste is not purely biological—it is also social. Humans are highly influenced by culture and environment. What one society considers a delicacy may be unthinkable in another. For example:

- Fermented foods: Natto in Japan or surströmming in Sweden have potent smells and flavors that may repel outsiders but are deeply cherished by locals.

- Spicy foods: Many people grow up avoiding chili heat, but in cultures where spice is commonplace, tolerance and enjoyment develop naturally.

- Bitterness and aging: Aged cheeses, cured meats, and wines require acquired appreciation, often taught through cultural rituals or social exposure.

Repeated exposure within a cultural context can transform initially unpleasant tastes into comforting or even desirable ones. This is why childhood experiences heavily shape which flavors are acquired versus rejected.

4. The Psychological Dimension of Acquired Taste

Psychology plays an equally important role. Humans are capable of conditioned taste preference, meaning repeated exposure can gradually increase acceptance and enjoyment of a flavor. Several mechanisms explain this phenomenon:

- Mere Exposure Effect: The more we encounter a taste, the more familiar it becomes, reducing initial aversion.

- Cognitive Association: Positive associations, such as a family gathering or a luxurious setting, can enhance flavor perception.

- Challenge and Novelty: Some individuals enjoy the thrill of conquering a “difficult” flavor, turning bitterness or pungency into a badge of sophistication.

Interestingly, the brain’s reward system adapts. Foods initially perceived as unpleasant can trigger dopamine release over time, signaling enjoyment after repeated consumption.

5. The Science of Complexity in Flavor

Acquired tastes are often associated with complexity. Complexity in flavor refers to layers of taste, aroma, and texture that unfold over time. Simple flavors, like sugar or salt, are immediately gratifying. Complex flavors, like those in blue cheese, espresso, or dark chocolate, demand more cognitive engagement.

- Flavor compounds: Foods with hundreds of volatile compounds provide nuanced taste experiences that may overwhelm the untrained palate.

- Bitterness and sweetness balance: Many acquired tastes, like dark chocolate, involve a delicate interplay of bitterness and residual sweetness, gradually rewarding repeated exposure.

- Fermentation and aging: Processes that transform raw ingredients into intricate flavor profiles often produce initially challenging aromas and tastes.

Thus, acquired tastes are often a testament to human capacity for sensory sophistication, allowing us to appreciate subtlety and depth that go beyond immediate gratification.

6. Childhood vs. Adult Taste Preferences

Taste preferences shift with age. Children are biologically wired to prefer sweet and avoid bitter, likely due to survival instincts. As adults, we gain the ability to appreciate complexity:

- Taste adaptation: Sensory receptors and neural processing can adapt over time, allowing for broader acceptance of flavors.

- Cultural exposure: Adults are more likely to travel, experiment with cuisines, or develop rituals that encourage adventurous eating.

- Cognitive maturity: Adults often understand and appreciate the cultural or artisanal value of certain flavors, adding psychological layers to the sensory experience.

This explains why some people struggle with coffee or black tea in youth but grow to savor them later in life.

7. Examples of Acquired Tastes Around the World

Let’s explore some classic examples to illustrate how biology, culture, and psychology intertwine:

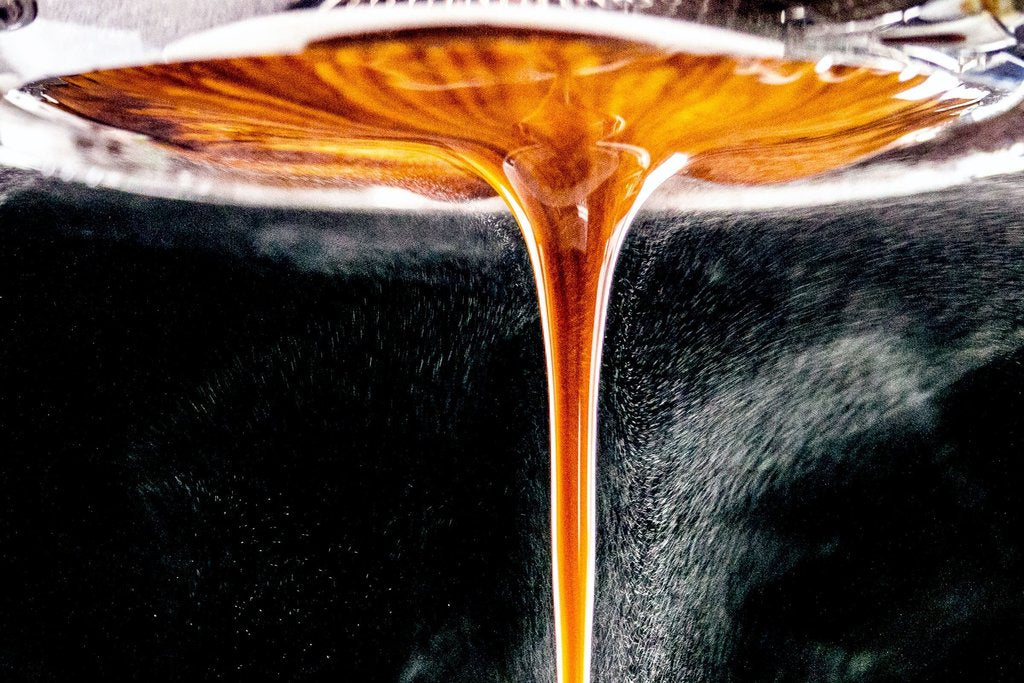

- Coffee: Bitter compounds initially repel many, but repeated exposure, caffeine effects, and cultural rituals foster global appreciation.

- Blue Cheese: Pungent aroma and strong flavor challenge the senses, yet fermentation creates complex textures loved by aficionados.

- Dark Chocolate: High cocoa content delivers bitterness and tannins; sweetness, texture, and aroma reward patient tasting.

- Fermented Vegetables: Kimchi or sauerkraut require tolerance for sour, salty, and umami notes.

- Alcoholic Beverages: Beer, wine, whiskey, and other spirits often combine bitterness, acidity, and complex aromas, rewarding repeated exploration.

- Spicy Foods: Capsaicin in chilies triggers pain and heat, but repeated consumption builds tolerance and enjoyment.

Each of these flavors reflects a delicate balance between initial biological resistance and the acquired ability to appreciate nuance.

8. The Pleasure of Mastering an Acquired Taste

Acquired tastes are deeply satisfying because they involve personal mastery. The journey from rejection to enjoyment creates a psychological reward:

- Sense of accomplishment: Appreciating a complex flavor can evoke pride or social admiration.

- Expanded sensory palette: Learning to enjoy challenging flavors enhances overall culinary literacy.

- Identity and distinction: Certain flavors become markers of cultural or personal sophistication, signaling adventurousness and openness.

Ultimately, the human capacity to acquire tastes underscores the interplay of biology, culture, and psychology in shaping our sensory world.

9. Practical Tips for Developing Acquired Tastes

If you want to expand your palate, the process is both systematic and enjoyable:

- Start mild: Begin with less intense versions of challenging flavors and gradually increase concentration.

- Pair wisely: Combine bitter or pungent foods with complementary tastes (e.g., dark chocolate with fruit, bitter greens with citrus).

- Repetition: Exposure over days and weeks reduces innate aversion.

- Mindful tasting: Focus on flavor notes, texture, and aroma rather than just the initial reaction.

- Social immersion: Enjoy foods in cultural or communal contexts to enhance cognitive and emotional associations.

With patience and curiosity, what once repelled you can become a treasured flavor.

10. Conclusion: The Art and Science of Acquired Taste

Certain flavors are considered acquired tastes because of a sophisticated interplay of biology, genetics, culture, psychology, and sensory complexity. Initial aversion is a natural defense mechanism, particularly against bitterness and pungency. Over time, repeated exposure, social reinforcement, cognitive association, and sensory refinement allow humans to not just tolerate but genuinely enjoy these flavors.

Acquired tastes celebrate the human ability to go beyond instinct, savor subtlety, and appreciate the richness of sensory experience. They remind us that taste is not merely consumption—it is a journey of curiosity, adaptability, and pleasure.

Whether it’s the sharp tang of blue cheese, the bold bitterness of espresso, or the fiery heat of chili, acquired tastes challenge our palates, expand our horizons, and reward our patience. In the end, they are a testament to the remarkable sophistication of human perception—and the joy of discovering new worlds through flavor.