When you sit down to enjoy a delicious meal or take a sip of your favorite drink, your senses are at the forefront of the experience. We often think of taste and smell as closely related, but which one actually plays a more prominent role in how we perceive flavor? Do your taste buds hold the upper hand, or is it your nose that is the true king of flavor perception? In this article, we’ll delve into the fascinating science of taste and smell, exploring how these two senses work together—and sometimes against each other—to shape our culinary experiences. By the end, you might just discover that your taste buds are not the most reliable judges after all!

1. The Power of Taste: A Sense of Simplicity?

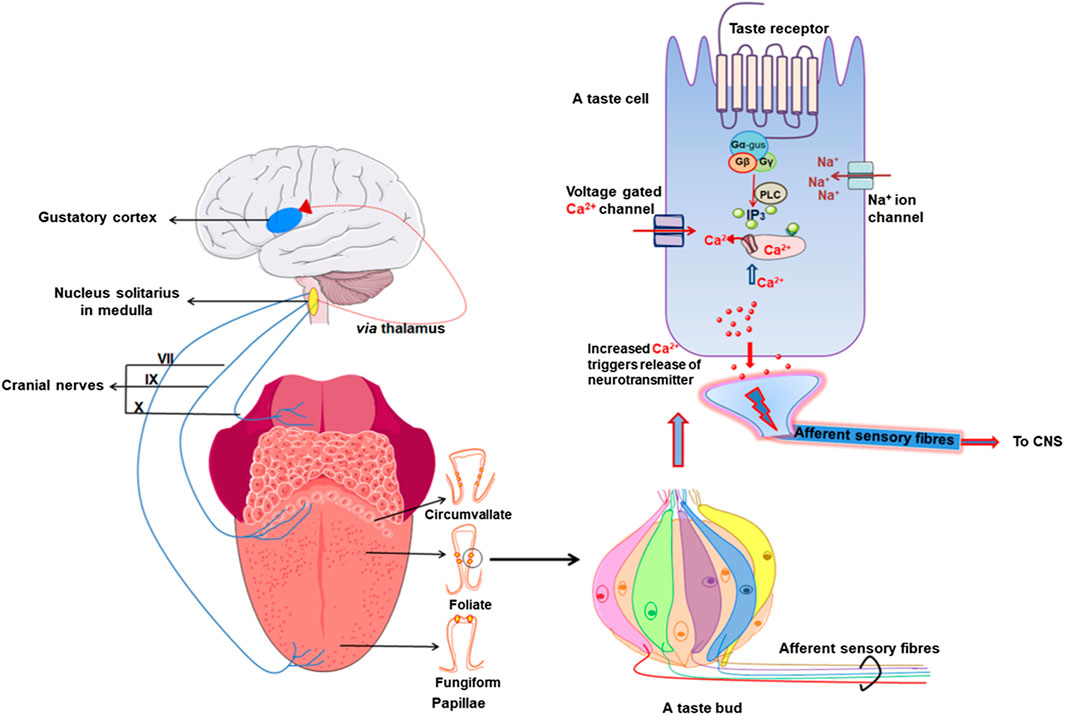

Taste, also known as gustation, is one of the five basic senses and often considered the simplest in comparison to the complex world of smell. Humans have taste buds located on the tongue, and these buds can distinguish five primary tastes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami (savory). The idea behind taste is relatively straightforward—each type of taste corresponds to specific chemicals in food that trigger the sensory receptors on your tongue.

Sweetness, for example, indicates the presence of sugars, signaling that the food may provide energy. Sourness can indicate acidity, which often signifies ripeness or fermentation. Saltiness suggests the presence of minerals, while bitterness is often a warning sign of toxicity. Umami, discovered in the 20th century, signals the presence of amino acids, typically in protein-rich foods.

Despite these distinctions, there is a major limitation to the sense of taste: it can only detect basic flavors. It doesn’t capture the complexity of the food as a whole, missing out on nuances that are critical to the overall flavor experience. This is where smell comes into play.

2. The Complexity of Smell: A Richer Dimension

Smell, or olfaction, is much more complex and is believed to contribute more to flavor perception than taste itself. The human nose can detect thousands of different odors—far more than the five basic tastes our tongues can sense. This heightened ability allows us to detect subtle aromas that significantly enhance or change the perception of food.

The science behind smell is intricate. When you inhale, odor molecules enter your nostrils and bind to olfactory receptors in the nasal cavity. These receptors send signals to the brain, which interprets them as distinct smells. But smell does not operate in isolation; it interacts with the other senses, especially taste. In fact, more than 80% of what we perceive as flavor is actually a combination of taste and smell.

For instance, when you eat an apple, your taste buds register the sweetness, but it’s the smell of the apple that adds layers of depth—whether floral, fruity, or slightly tart—creating the complete sensory experience. This is why food can taste “bland” when you have a cold or a stuffy nose; without the ability to smell, your brain has far less information to create the full flavor profile.

3. How Taste and Smell Work Together

While both taste and smell can operate independently, they are most powerful when working in harmony. The connection between the two senses is so strong that a change in one often results in a change in the other. This synergy is most clearly evident in what’s known as “flavor,” which is the complex combination of both tastes and smells that we experience when consuming food.

Take the example of a chocolate bar. Your taste buds will pick up on the sweetness and richness, while your nose will register the cocoa’s deep, slightly bitter aroma. The brain then merges these signals into a single, coherent experience—the flavor of chocolate. However, if your sense of smell is impaired, you might taste the sweetness of the chocolate but miss the full richness and depth that smell provides.

Interestingly, research has shown that smell can also influence taste in more unexpected ways. For example, a study found that people tend to perceive wine as being “sweeter” when it’s paired with a certain aroma, even if the wine itself has no added sugar. This is called flavor enhancement and demonstrates how the brain integrates signals from different senses to create a complete experience.

4. When Taste and Smell Go Wrong: The Role of Anosmia

Anosmia is the loss of the sense of smell, and it can have a profound effect on how we experience food. Those with anosmia often report that food tastes flat or uninteresting, as the loss of smell severely diminishes the richness of flavor. Imagine eating a dish that should be vibrant and flavorful, but because your nose can’t detect any of the aromatic compounds, it seems like you’re just chewing on bland textures.

Even when someone doesn’t have complete anosmia, partial loss of smell (hyposmia) can alter taste perception, making it harder to distinguish between different flavors. This is why people with cold or flu symptoms often find that food doesn’t taste the same, and why food becomes dull and less appetizing when you have a blocked nose.

Interestingly, people who lose their sense of taste—known as ageusia—experience a similar issue. Without the ability to perceive sweet, salty, sour, or bitter flavors, food is reduced to its texture and temperature. The loss of taste can severely impact a person’s quality of life, as eating becomes more of a mechanical act rather than an enjoyable sensory experience.

5. Taste vs. Smell: Which Is More Accurate?

If we had to pick a winner between taste and smell, it’s clear that smell holds the advantage when it comes to the richness and accuracy of flavor perception. The tongue’s taste buds are limited to the basic categories of sweetness, saltiness, sourness, bitterness, and umami. However, the nose can detect a vast array of complex aromas, allowing it to convey the full spectrum of flavors, from the subtle sweetness of a ripe strawberry to the savory depth of a well-aged cheese.

Moreover, studies have demonstrated that the brain is more reliant on smell than taste for flavor perception. For instance, people can often recognize familiar foods simply by their smell, even before they taste them. Similarly, a study by the Smell and Taste Treatment and Research Foundation found that individuals with anosmia had a significantly reduced ability to distinguish between different food flavors, further emphasizing the role that smell plays in overall flavor perception.

6. Why Your Nose Might Be Your Most Accurate Sense

While taste plays a crucial role in detecting basic flavors, it’s your nose that provides the most accurate and detailed information about the food you’re consuming. The variety of scents you encounter not only determines the food’s flavor profile but also triggers emotional responses. For example, the smell of freshly baked bread might evoke feelings of comfort, while the scent of freshly brewed coffee may make you feel energized.

Smell is also deeply linked to memory. A particular aroma can transport you back to a moment in time, evoking vivid memories associated with that scent. This connection between smell and memory is a testament to how powerful and meaningful our olfactory experiences can be.

In fact, researchers have discovered that people with a more developed sense of smell tend to have better overall taste perception. The nose can detect subtle flavor notes that the tongue cannot, enhancing the overall eating experience.

7. Conclusion: Trust Your Nose for the Best Flavor

While both taste and smell are vital to our experience of food, it’s clear that your nose plays the more accurate and influential role in shaping flavor perception. The interplay between taste and smell is what makes food enjoyable and exciting. So next time you savor a meal, take a deep breath and appreciate the aromas that make it truly special. You might just find that your sense of smell has been your most reliable guide all along.