Taste is one of the most fundamental human experiences. It influences our daily choices, guides us in nourishment, and serves as a conduit for enjoyment or disgust. But beneath the surface, the nature of taste is a bit more complex than simply a biological reaction to food. It begs the question: Is taste purely a biological response, or is it, in part, a psychological trick? The answer, as we will explore, lies at the intersection of biology, psychology, and culture.

The Biological Basis of Taste

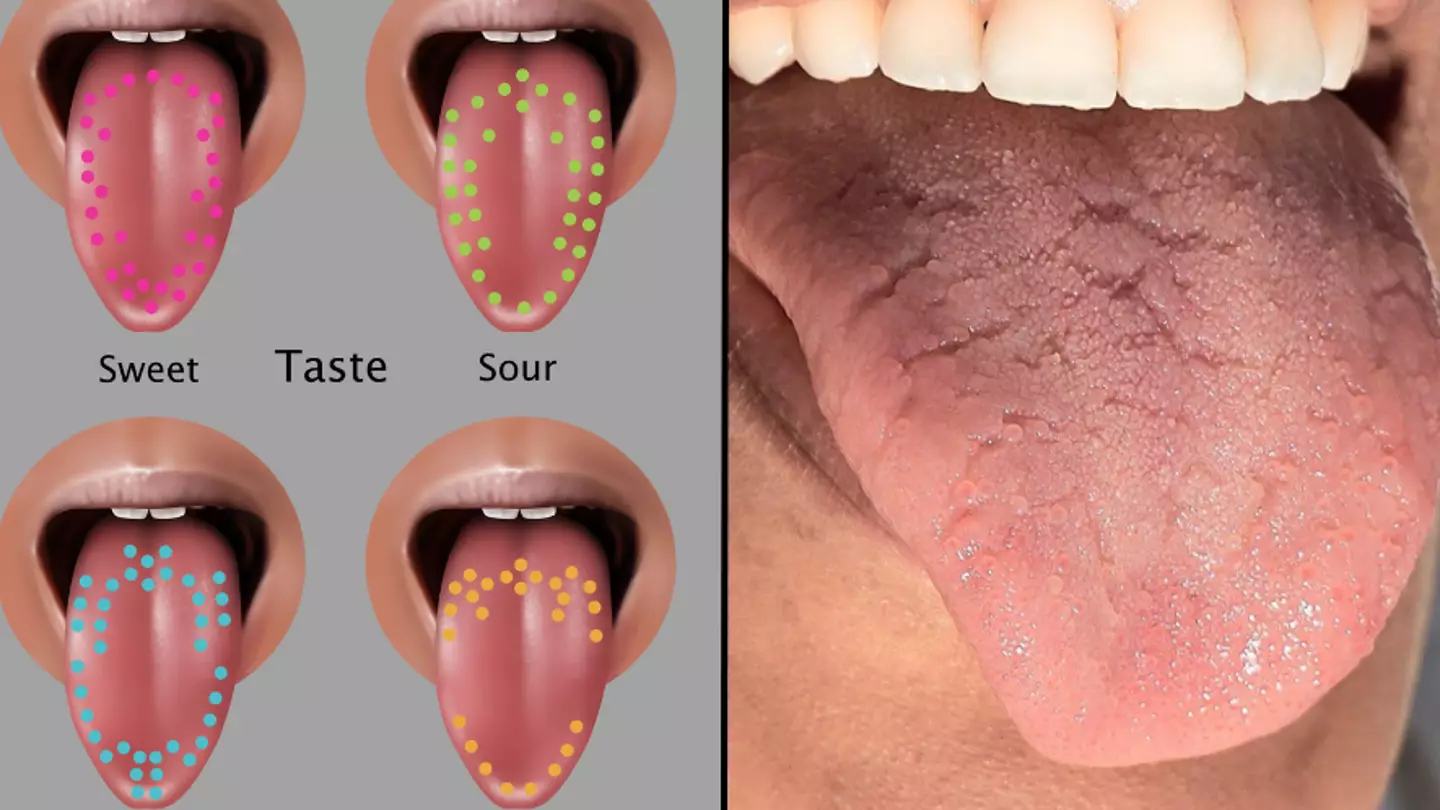

At its core, taste begins with our biology. Our sense of taste relies on specialized cells called taste receptor cells, which are located in the taste buds on the tongue. These receptor cells are responsible for detecting different compounds in food, which are then processed by the brain to produce a “taste” sensation. There are five primary tastes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. Each of these tastes corresponds to the presence of specific chemical compounds, such as sugars, salts, acids, alkaloids, and glutamates.

When you eat, molecules from the food interact with the taste receptors on your tongue. These receptors are activated, and signals are sent to the brain. The brain processes these signals in the gustatory cortex and identifies the “flavor.” This process is purely biological and happens quickly, almost reflexively. However, it is only the beginning of the complex experience that is “taste.”

The Role of the Brain in Taste Perception

While the initial sensory input comes from the tongue, taste is not just a simple biological response. The brain plays a crucial role in interpreting and enhancing this experience. The gustatory cortex, the part of the brain responsible for taste, is connected to several other regions involved in memory, emotion, and smell. This is where the psychological factors start to come into play.

For instance, the way we perceive a flavor can be influenced by our past experiences. If you’ve had a bad experience with a particular food, your brain might associate that food with a negative emotion, leading to an aversion that overrides the biological signals of taste. Conversely, positive experiences, such as enjoying a meal in a comforting setting, can make a food taste more enjoyable than it might in a neutral or stressful environment.

Furthermore, our expectations can dramatically shape our taste perceptions. A study conducted by researchers at the University of London demonstrated that people rated wine as tasting better when they were told it was more expensive, even if it was actually a cheaper variety. This suggests that psychological factors, such as pricing and branding, can alter the way our brain processes the taste of food. In essence, our brain is not just reacting to chemical stimuli but is also interpreting those stimuli through a complex lens of memory, emotion, and expectation.

Taste and Smell: The Dynamic Duo

One of the most powerful psychological tricks influencing taste is the interplay between taste and smell. Although taste and smell are technically separate senses, they are deeply interconnected. The olfactory bulb, which processes smell, is closely linked to the gustatory cortex. In fact, much of what we perceive as “taste” is actually influenced by our sense of smell. When you eat something, volatile molecules from the food travel to the olfactory receptors in the nose, sending signals to the brain. This process, called retronasal olfaction, is what allows you to experience the full flavor of food.

Consider the example of eating an apple. You can taste the sweetness and acidity of the fruit with your tongue, but much of the distinct flavor comes from the smell. If you were to eat the same apple while holding your nose, you would notice that the taste is far less pronounced. This illustrates just how much our perception of flavor is reliant on psychological factors like smell. The brain integrates sensory information from both the taste and smell receptors, creating a unified experience of flavor.

The Influence of Culture and Environment

The psychological tricks that influence taste are not limited to personal experiences and expectations. Cultural factors play a significant role in shaping our tastes as well. What is considered a delicacy in one culture may be unappealing in another. For example, fermented foods like kimchi or sushi are loved in many Asian cultures but might be off-putting to individuals unfamiliar with those flavors.

Environmental factors can also shape our taste perceptions. The ambiance of a restaurant or the presentation of a dish can affect how we perceive the flavors of the food. Studies have shown that people tend to rate food as tastier when it is served in a visually appealing manner. The same dish might taste better when presented on a beautifully arranged plate compared to when it is served on a plain, unattractive dish. This highlights how psychological factors, such as the visual appeal of food, can influence our sense of taste.

Moreover, the context in which food is consumed can alter its flavor. A warm bowl of soup on a cold winter’s day will likely taste much more satisfying than the same soup eaten on a hot summer afternoon. The physical and emotional context in which we experience food profoundly influences how we perceive its taste.

The Psychological Tricks of Taste Enhancement

Food manufacturers have long understood the power of psychology in taste perception. This is why food products are often engineered with flavor-enhancing ingredients like monosodium glutamate (MSG), artificial sweeteners, and other additives that trick our taste buds into perceiving a richer, more satisfying flavor. These additives manipulate the brain’s responses to food, often bypassing the biological mechanisms of taste to create a more pleasurable experience.

In addition, marketers use sensory cues to enhance taste perception. Packaging colors, product names, and even the sounds associated with food (like the crunch of a potato chip) can all influence how we perceive the taste of a product. For example, research has shown that people are more likely to describe a snack as “crispy” or “crunchy” if they hear a crunching sound while eating, even if the food is not particularly crunchy. This psychological association between sound and taste can alter the perception of flavor in a significant way.

The Evolutionary Perspective: Why Taste Matters

From an evolutionary standpoint, taste has developed to serve a critical survival function. Our ability to detect bitter tastes, for example, is thought to have evolved as a mechanism to avoid toxic or poisonous substances. Likewise, the preference for sweet foods is believed to be linked to the high energy content of sugars, which were valuable resources for early humans. The taste for salty foods likely emerged due to the need for essential minerals like sodium for bodily functions.

However, in the modern world, these evolutionary instincts may no longer align with our current environment. The abundance of highly processed and artificially enhanced foods challenges our innate taste mechanisms. The foods that taste “good” to us—often sweet, salty, and fatty—are not always the healthiest choices. This disconnect between our evolutionary preferences and modern food availability has contributed to the global rise in obesity and other health issues.

The Future of Taste: Can We Control It?

As science advances, it’s becoming clear that taste is not only shaped by biology and psychology but also by technology. New innovations, such as taste-altering devices and food engineering, may soon enable us to directly manipulate our sensory experience of taste. For instance, “electro-tongues” are being developed to stimulate taste receptors using electrical signals, potentially allowing us to experience a broader range of flavors without the need for actual food. Similarly, researchers are experimenting with virtual reality (VR) to alter the perception of flavor, using sight and sound to trick the brain into “tasting” something that isn’t actually there.

These advancements suggest that the boundaries between biological response and psychological trickery in taste will continue to blur, and we may soon have the ability to control and enhance our gustatory experiences in unprecedented ways.

Conclusion

Taste is neither solely a biological response nor merely a psychological trick—it is a complex interaction between the two. The biological mechanisms that detect and process flavors are essential, but our brains, memories, expectations, and even the environment we’re in all play a profound role in how we perceive and experience taste. Whether we are savoring a meal or turning our nose up at something unfamiliar, it is clear that taste is not just something we passively experience. It is a dynamic process, influenced by both our biology and our psyche. As we continue to explore the intricate relationships between biology, psychology, and culture, we gain a deeper understanding of this essential sense—and perhaps even learn how to manipulate it for our own enjoyment.